The seeds of dissent in the Colonial Caribbean

Researched and written by Daniel Townsend

The battle to gain recognition and remembrance for Britain’s Imperial forces has been a drawn out process and indeed, one that is still ongoing in many ways. Though the ‘Baptism of Fire’(1) faced by ANZAC forces in Gallipoli proved a nation building exercise for Australia and, through the work of the media as well as scholars like Al Thompson(2) has become embedded within dominant narratives of the war in both Australia and to an extent in Britain, the contribution of other countries- such as those in the Caribbean- remains marginalized within the annals of history.

While one cannot claim that there has been no research on the subject it is evident that this work has not entered public consciousness in a way that challenges pre-existing narratives of the war. Research in to the field has been hampered by a number of incidents, notably after the First World War the government decided that keeping various records relating for instance, to hospitalization of soldiers, was unnecessary and ordered them to be destroyed. Of the records that were deemed useful enough to maintain many were destroyed during a Luftwaffe raid in 1940 when an incendiary bomb hit the War Office Record Store on Arnside Street, London- these are now referred to as ‘Burnt Documents’(3).

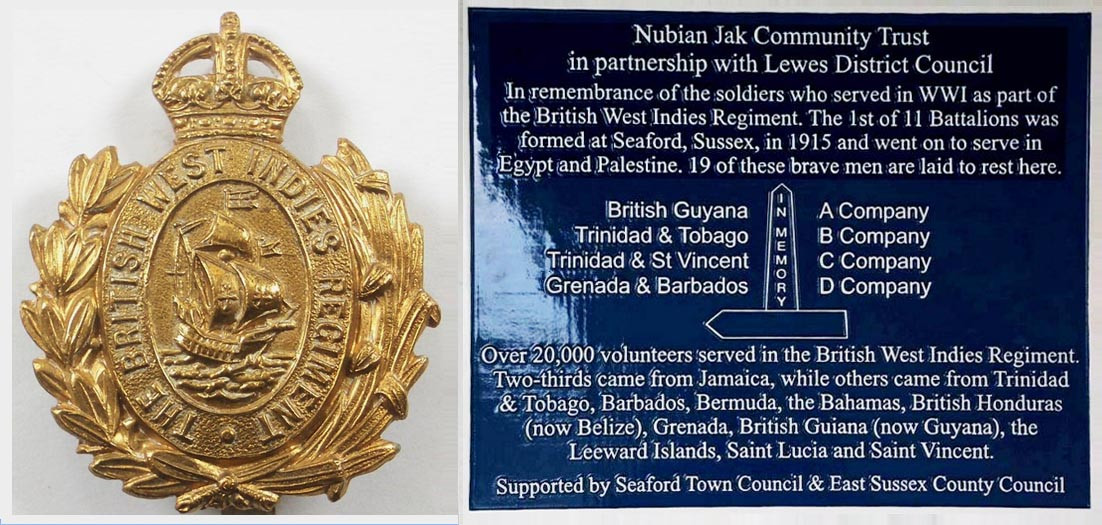

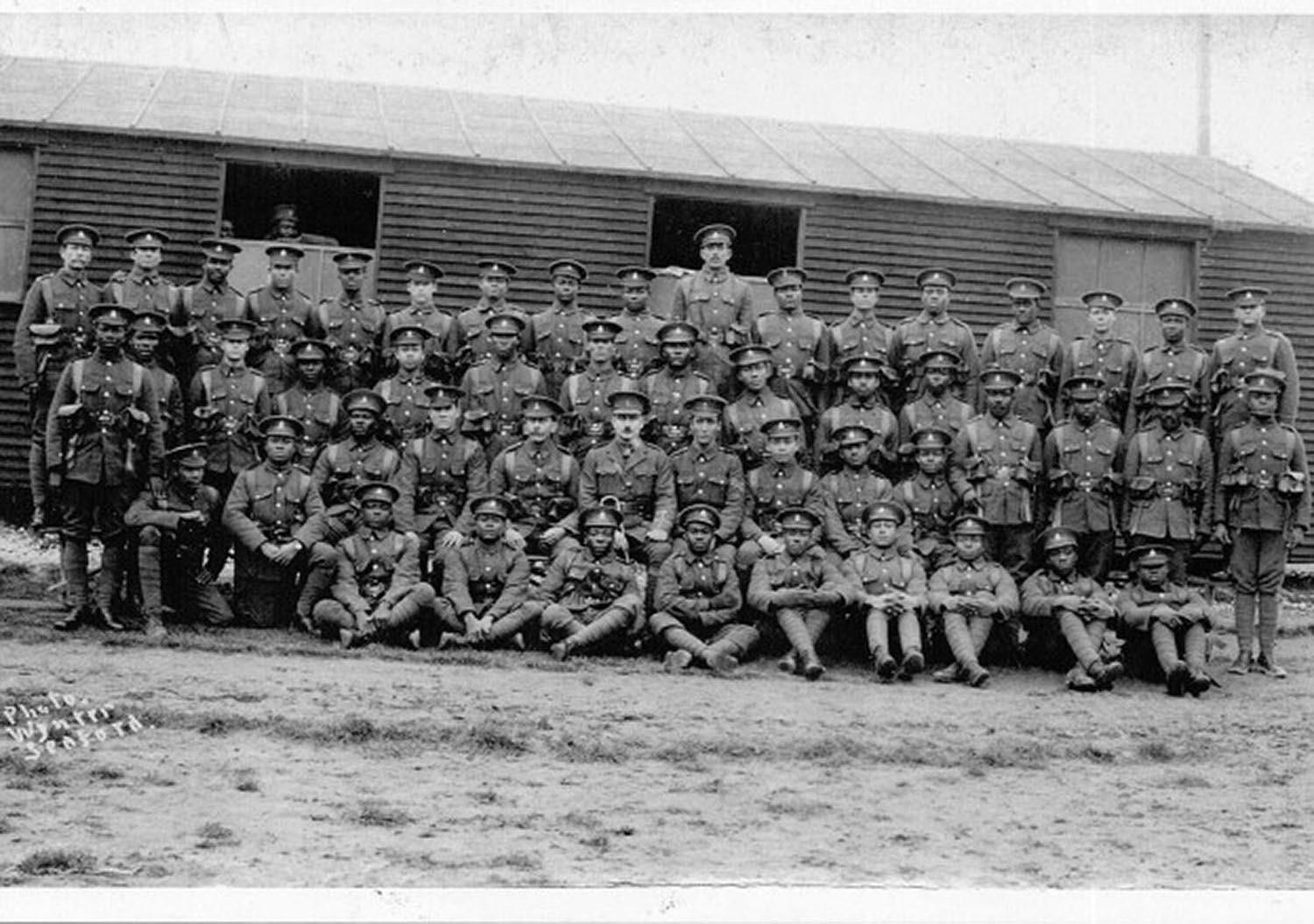

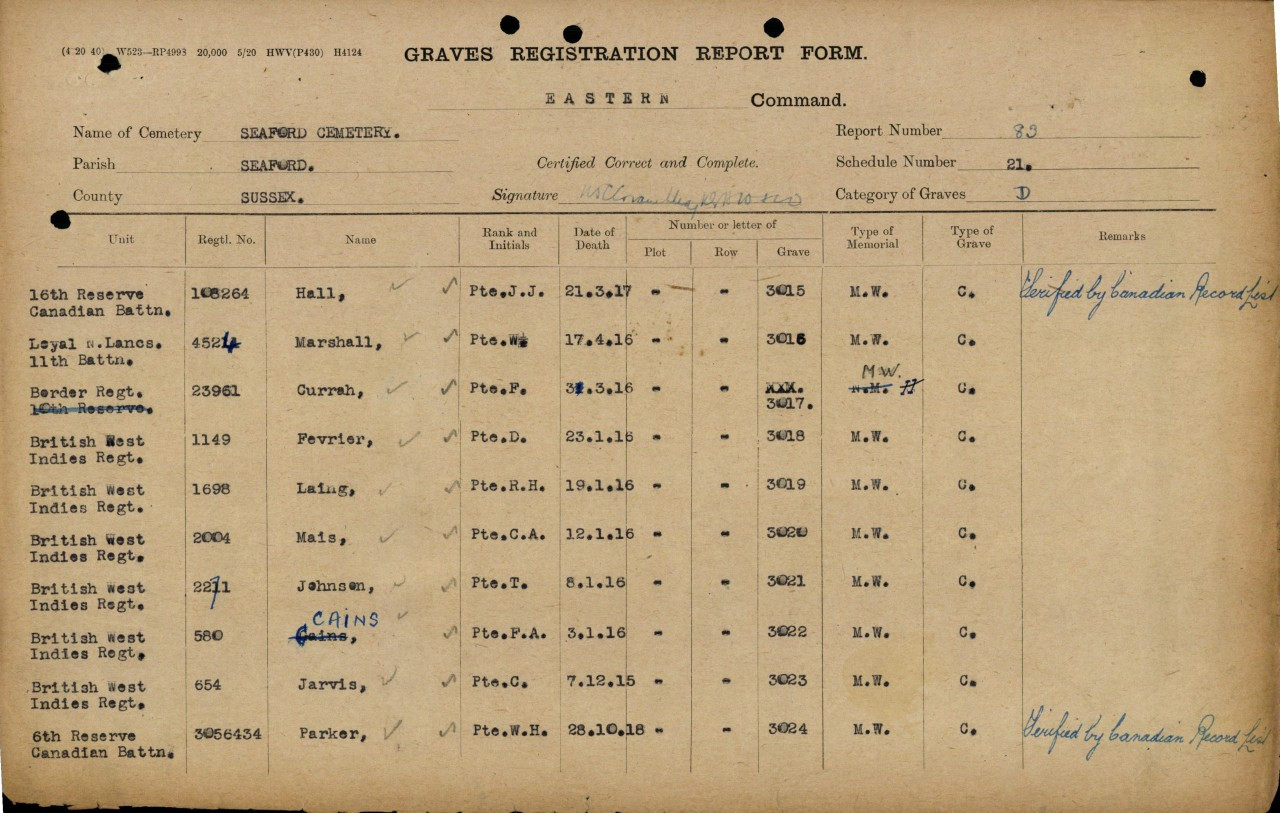

Focusing on the British West Indies Regiment (hereafter abbreviated to BWIR), stationed in Seaford from 1916 one can see the correlation between the lack of research and the lack of memorialization. Their first memorial in Seaford, with the notable exception of the nineteen BWIR graves in Seaford Cemetery, came as late as 2015 in the form of a plaque on Cemetery Chapel. The newest memorial to this regiment was installed in 2018 at Seaford railway station, commemorating their centenary. Thus their journey throughout the war: from the Caribbean to Sussex and then to either the western or Palestinian fronts is an intriguing tale, and one that is underreported.

Recruiting the BWIR

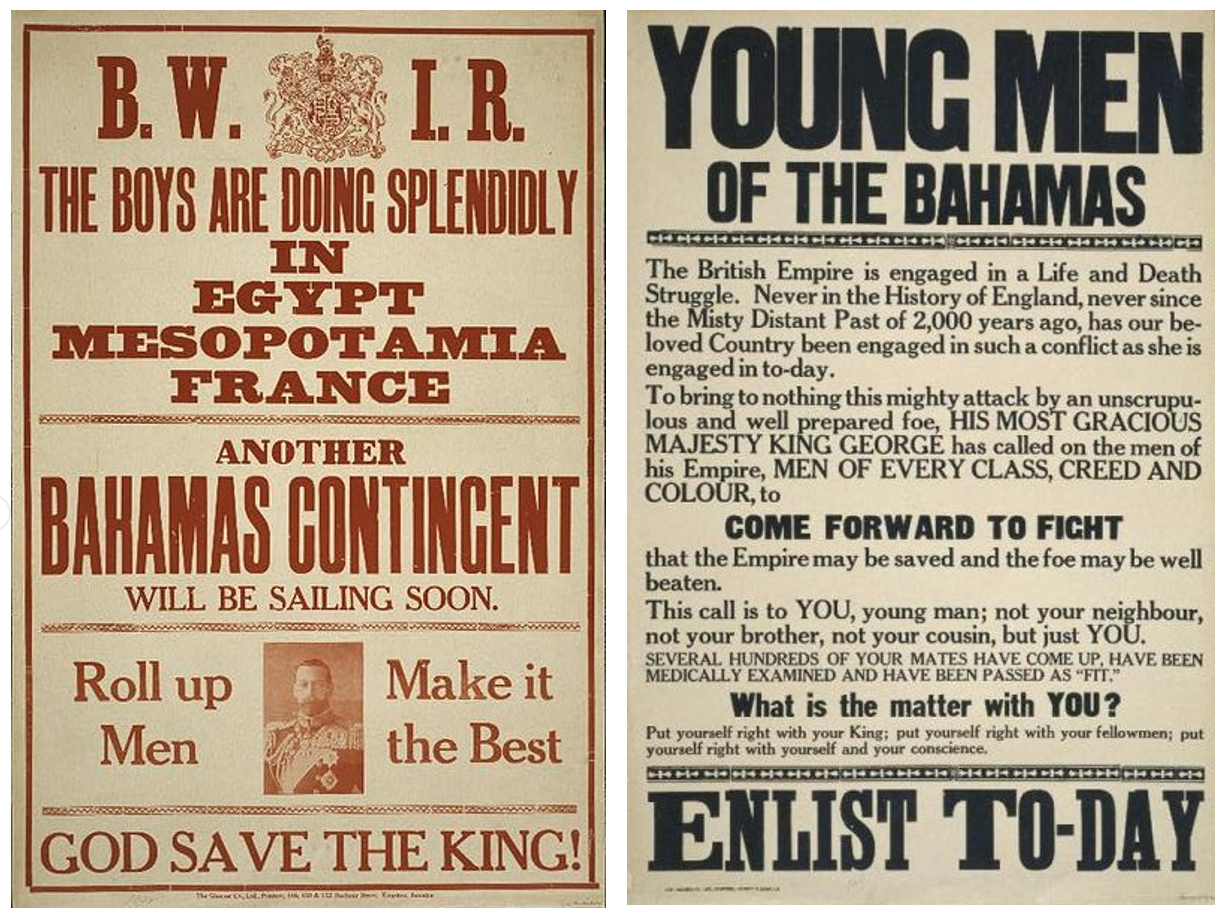

At the outbreak of war, though the British Government and the War Office gladly accepted the contribution of money and goods from Caribbean countries, there was a reluctance to raise troops from the West Indies. The call of King George V that “men of every class, creed and colour” must fight was one that was not heeded with any enthusiasm by the war office, which “did not want black men in its army”(4). Indeed, it took a second decree from the King in October 1915 for the War Office to relax its stance, allowing the recruitment of the BWIR to begin in earnest.

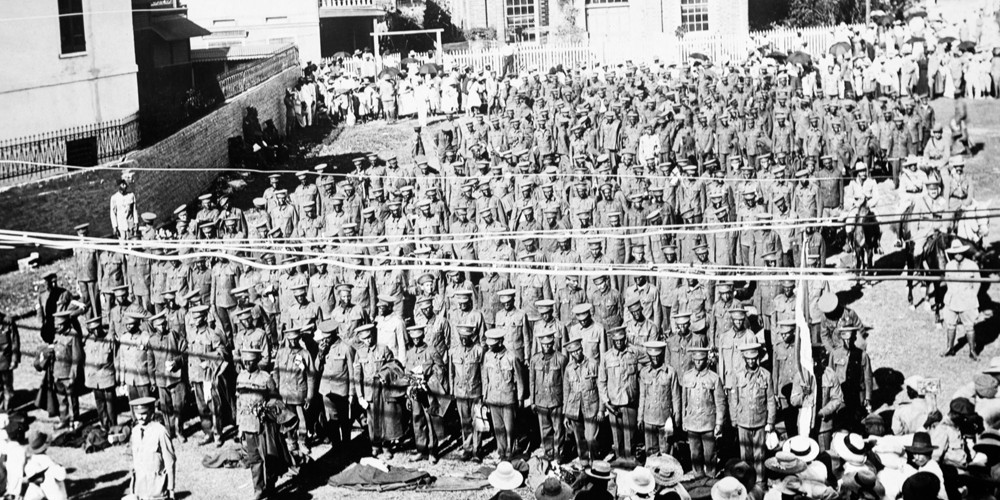

Conscription was never used in the West Indies as it was in Britain. Indeed, there was little need for such measures.

Following the outbreak of war a wave of patriotism availed itself across much of Britain’s Empire, encouraging many young men to volunteer to supplement the British Expeditionary Force in Europe.

Glenford Howe, writing for the BBC, notes that the attrition of “remnants of African cultural practices” as well as the “proliferation of British institutions, culture and language”(5) throughout the Caribbean under British rule were contributing factors in the willingness of many to volunteer in the war effort. George Blackman, a BWIR veteran of WWI, recalls the feelings of loyalty cultivated within the Caribbean at this time:

“We wanted to go. Because the island government told us that the King said all Englishmen must go to join the war. The country called all of us.”(6)

While the willingness to identify with this notion of ‘Black Britishness’ was clearly an important motivating factor within the decision of many to join the BWIR, the government also utilized other methods. Typical propaganda posters, such as those from the Bahamas pictured below, offer personal appeals to enlist for ‘your King… your fellowmen… your conscience’; large recruitment meetings focused on traditional war tropes, arguing that joining the army brought discipline, exercise and glory.

The result was 15,600 men recruited, who would be formed into 11 battalions.

Transporting the BWIR to Britain

If the sinking of the Titanic in 1912 hadn’t served to highlight the potential perils of transatlantic voyages then the war would.

The German Navy’s new Unterseeboot or U-boat would sink more than 5,000 ships during the course of the First World War and was just one of many obstacles that troop ships faced on their long journey from the Caribbean to English ports. Though the British Navy employed techniques to counter the threat of U-boats in the North Sea and Atlantic they remained a prominent issue for troop ships and, indeed, it was this fear that led to what is now referred to as the ‘Halifax incident’.

The 3rd Jamaican contingent of the BWIR, consisting of 25 officers and 1,115 other ranks was due to sail on the SS Verdala departing from Kingston, Jamaica on 6th March 1916. It was feared that U-boats were operating along her route and hence the Verdala was diverted at short notice to the closest allied port, where it was instructed to wait until the passage was deemed safe. Given the frequent operation of the German Navy in and around Irish ports and the fact that the USA were a neutral party at this juncture in the war the Canadian port at Halifax, Nova Scotia was chosen as the Verdala’s destination.

The troubles of the SS Verdala and the soldiers on board began while en route to the Canada. The ship encountered blizzard conditions in the Western Atlantic, freezing water pipes and covering the decks with ice and snow(7). Both the men and the ship were ill-equipped to deal with the onslaught of cold weather, the inadequate heating of the Verdala further exacerbating the conditions of the troops whom had not been supplied with winter uniforms.

During their relatively short journey and their subsequent stay in Nova Scotia approximately six hundred men suffered from exposure and frostbite(8). The worst cases were landed in Halifax- one hundred and six of whom required amputations to their affected limbs(9) and five of whom died.

Though this case of ill preparedness on the side of the British Navy proved to be an isolated incident it was arguably indicative of the lackluster treatment afforded to West Indian troops by the War Office. Though Frank Cundall is adamant that the return of ill, unfit and maimed soldiers had little effect on the Jamaican desire to participate in the war, one can infer that the return of 391 members of the 3rd contingent, who had never even made it to Europe(10), had a lasting effect on those Jamaicans who were looking for reasons to oppose British rule and promote self-governance.

Training in Seaford

Following their journey across the Atlantic, the various battalions of the BWIR were dispersed across the country for training. It was the 1st Battalion who had the dubious pleasure of being stationed in Seaford.

The battalion war diary indicates that they arrived in Seaford on November 25th, 1915, with 725 rank and file under the command of Major Neish. Though there is little contemporaneous material that indicates the reaction of the local population, we are told that there was a universally positive response, with many commenting on their “good discipline and excellent conduct”(11).

This is unsurprising; upon their arrival in Seaford the BWIR were treated to a large dose of British weather, with many of their initial training drills unable to take place as a result. The unrelenting weather quickly created muddy conditions across the the camp and surrounding countryside and training was reduced to marching, small-scale drills and lectures(12).

This lack of activity lessened the potential impact that a 800-strong group of young men might have on the town.

Unfortunately, the most notable part of the 1st Battalion’s stay in Seaford are the illnesses that swept across their camp during the latter part of 1915 and the beginning of 1916.

If the drastic changes in climate already put the men at risk, the unfavorable weather and poor barracks in which they were housed meant that, for many, the stay in Seaford was unpleasant and short-lived. Convalescence centres in Seaford, Eastbourne and Newhaven were soon full of soldiers suffering from pneumonia and similar diseases, with a later epidemic of mumps only adding to their troubles.

Though the medical officers worked “heroically all day and most of the night”(13) to save soldiers, the inadequate provision of supplies and vital medications as well as the sheer number of admitted men meant that many died in these centres or were invalided out of the war.

In total, nineteen members of the BWIR who died in various military hospitals and convalescence centres across Sussex are buried in Seaford Cemetery.

During the First World War the non-repatriation of the dead was common practice, largely due to the sheer number of those killed and buried. Transporting their bodies often across oceans would have been a logistical nightmare that a country engaged in a total war could ill afford. Moreover, while some families could afford the transportation and burial of a loved one, many could not.

Soldiers were generally buried in or near their place of death, serving to explain the haphazard placement of war graves sites across parts of Belgium and France, generally the locations of field hospitals just behind the front lines - the size of the graveyard being a measure of how bloody was the battle fought there.

Western Front

After completing their training, the BWIR moved to active service on the Western front.

While many men had presumed they would end up fighting on the front lines, the war office decided that only white soldiers were fit to fight, relegating member of the BWIR to the labor service on the grounds that it was “against British tradition to employ aboriginal troops against a European enemy”(14).

This policy of racism, largely upheld to prevent the Germans from believing the “empire needed the help of savages”(15) to win the war, meant that the job of the BWIR in France involved digging trenches, bearing stretchers, loading and unloading ships and trains and working in ammunition dumps, rather than engaging in combat. Of course, the decision of the British Government not to allow the BWIR to take part in the fighting didn’t mean they were safe from enemy fire. Indeed, Field Marshal Haig issued a statement of thanks in 1917 wherein he commended them for carrying out such arduous work under “almost continuous shellfire”(16).

The bitterness felt by the BWIR at being pushed in to a support role while still under fire is emphasized within the war poem ‘Black Soldier’s Lament’(17):

Stripped to the waist and sweated chest,

Midday’s reprieve brings much needed rest.

From trenches deep toward the sky

Non-fighting troops and yet we die.

Indeed, despite the praise heaped upon the BWIR for their service they were still the subjects of racism and an outlet for frustration for some British troops. The testimony of one Corporal Samuel Alfred Haynes recalls a group of black soldiers singing ‘Rule Britannia’ before being confronted by a white soldier who asked “who gave you niggers authority to sing that, clear out of this building - only British troops admitted here”(18).

The idea that all were equal in the King's army and all were equal in the fight against the Germans was one that was no upheld in attitudes to black soldiers on the Western Front. Even German prisoners were witnessed spitting on their hands and wiping their faces “to say we were painted black”(19).

Palestine and Egypt

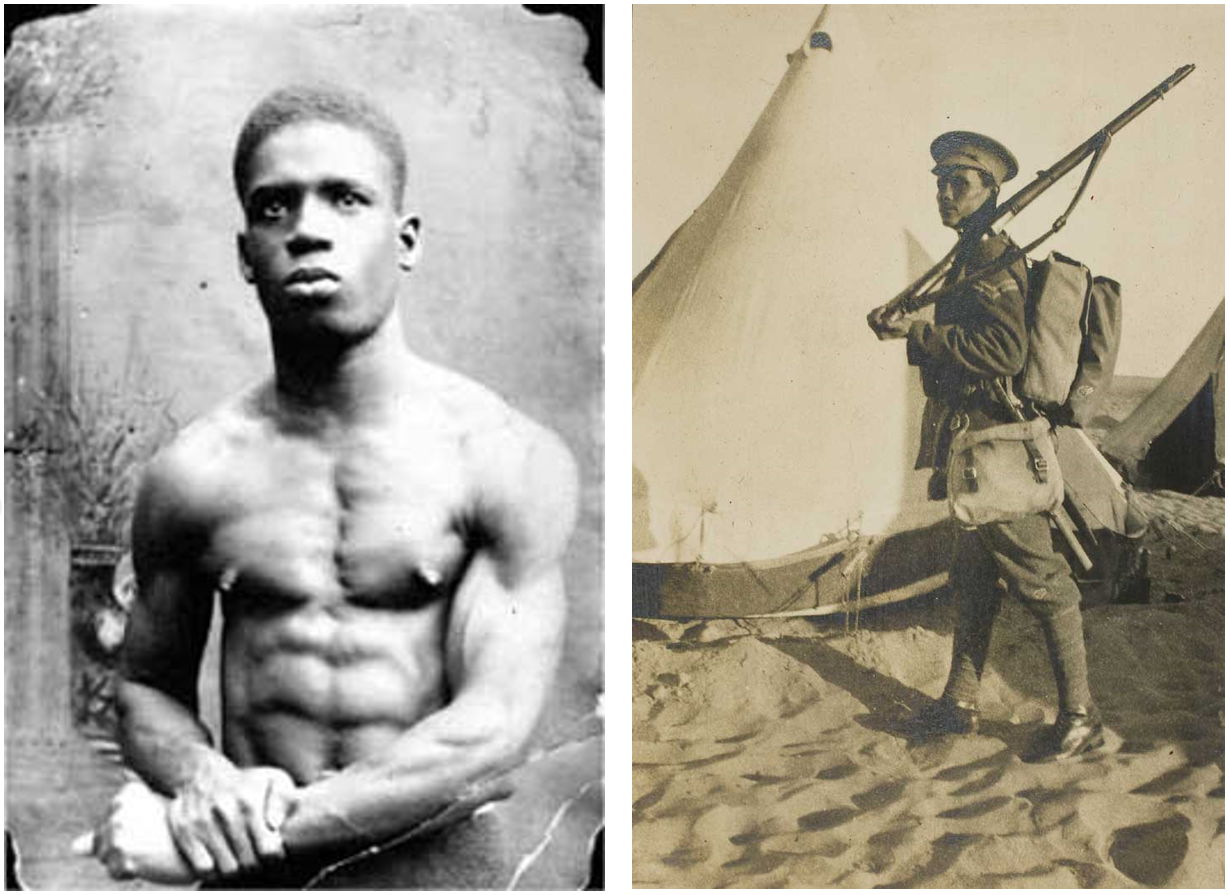

Though they were not permitted to fight on the Western Front, the 1st, 2nd and 5th battalions of the BWIR saw fighting during their active service in the east, against the Turkish army.

Much like their time in France, the decision to allow the BWIR to fight in the eastern theatre was informed largely by race. While there was opposition to fielding ‘savages’ against a European army, it was considered much more acceptable to field a native army against other savages, such as the Turks.

It is evident that being part of the fighting force wasn’t the result of an increased respect for West Indian soldiers: “we are treated neither as Christians nor as British citizens, but as West Indian niggers without anybody to be interested in nor look after us”(20)

Despite the skepticism still held by many in the War Office and the racism still faced by members of the BWIR on a daily basis, their hard-fought victories against the Turks bought them plaudits from their commanders.

The BWIR fought with bravery in various crucial battles in the Eastern Theatre, crossing open land under heavy fire and capturing key points previously held by the “ferocious”(21) Turkish army. Winston Churchill Millington (pictured below) was awarded a distinguished combat medal for bravery as a result of his fighting with the machine-gun section of the BWIR 2nd Battalion. The changing attitudes among many to the presence and participation of West Indian troops is exemplified in General Allenby’s letter to the Governors of Jamaica:

“I have great pleasure of informing you of the excellent conduct of the machine-gun section of the British West Indies Regiment during two successful raids on the Turkish trenches. All ranks behaved with great gallantry under heavy fire, and contributed in no small measure to the success of the operation.”(22)

Taranto Mutiny

In the aftermath of the armistice, signed in November 1918, parts of the BWIR were moved to a training camp in Taranto, Italy.

The issuing of Army Order No.1, an edict that granted an additional sixpence in pay to members of the armed forces, caused divisions and tensions within the camp when the decision was made to apply this order only to white soldiers, on the basis that members of the BWIR had been classified as ‘natives' (23) and were thus not entitled to it.

The continuing gulf between the treatment of white and black troops caused further resentment: awaiting demobilization, the West Indian troops were forced to continue to perform laborious duties, such as the loading and unloading of ships and the cleaning of latrines, while white troops spent their time in cinemas and the YMCA, places that were off-limits to ‘coloured troops’(24)

It was this derisory treatment of black troops that ignited the spark of mutiny, men of the 9th battalion attacking their officers in a revolt that would require four days, and the arrival of a fighting fit battalion of the Worcestershire Regiment, to be quelled.

Though the uprising in Taranto was swiftly dealt with and its perpetrators punished, it had served to sow the seeds of long-term bitterness against the British Empire, “stimulating the development of black nationalism in the British Caribbean”(25).

The British Government were wholly aware of the ramifications of the mutiny. The words of one sergeant Baxter (himself a participant in the mutiny) that “the black man should have freedom and govern himself in the West Indies and if necessary force and bloodshed should be used to attain that object”(26), serving to ring alarm bells within the upper echelons of colonial offices. Indeed, this fear was laid out within a secret colonial memo from 1919, which asserted “nothing we can do will alter the fact that the black man has begun to think and feel himself as good as white”(27).

This new-found fear of revolution in the colonies by agitation from demobilized and politically conscious ex-members of the BWIR, led to a series of decisions from the government regarding the transportation of these men back to the Caribbean.

Rather than returning many black troops to their homes, they were repatriated to other countries such as Cuba and Venezuela, where they would have to use their own means to return to their countries of origin.

It is estimated that around 4,000 soldiers were displaced in this manner. The difficulty of tracing them makes it impossible to know exactly how many were able to return to their countries. Indeed, George Blackman - a war veteran from Barbados - went off the radar while living in Colombia and Venezuela, not returning to his native country until 2002(28).

Despite the precautions taken by the Colonial Offices, agitation and demonstrations still took place across parts of the British West Indies in the year after the war. 1919 saw campaigns in British Honduras (now Belize), and Trinidad - arguably the beginning of the end for absolute British rule in the region.

Though independence for these countries did not occur until 1964 (Belize) and 1962 (Trinidad), the root of their liberation can be found within the new consciousness coming out of the First World War.

Sources

‘Caribbean participants in the First World War’. Memorial Gates Trust mgtrust.org accessed 7/8/18

Cundall, Frank. Jamaica’s Part in the Great War 1914-1918. London: West India Committee, 1925.

Elkins, W. F. ‘A Source of Black Nationalism in the Caribbean: The revolt of the British West Indies Regiment at Taranto, Italy.’ Science in Society 34:1 (1970): P.99-103.

Howe, Glenford D. ‘A white man’s war? World War One and the West Indies’. BBC.co.uk 10/3/11 accessed 7/8/18

Johns, Steven. ‘The British West Indies Regiment Mutiny, 1918’. Libcom.org 7/8/13 accessed 7/8/18

Lennon, Peter. ‘Dishonoured Legion’. The Guardian 7/10/99 accessed 8/8/18

‘Lest We Forget- The British West Indies Regiment’. Grenadanationalarchives.wordpress.com 1/1/14 accessed 7/8/18

Peatfield, Lisa. ‘How the West Indies helped the war effort in the First World War’. Iwm.org.uk 8/6/18 accessed 7/8/18

Peatfield Lisa. ‘The Story of the British West Indies Regiment in the First World War’. Iwm.org.uk 8/6/18 accessed 7/8/18

Rogers, Simon. ‘There were no parades for us’. The Guardian 6/11/02 accessed 8/8/18

References

(1) Paul Keating’s speech, Sydney Morning Herald 31/10/08

(2) e.g. the film Gallipoli, the importance of ANZAC day as a national holiday, and works such as Anzac Memories by Alistair Thompson

(3) War Office: Soldiers’ Documents, First World War ‘Burnt Documents’’. National Archive http://discovery.nationalarchives.gov.uk/details/r/C14567 Accessed 8/8/18

(4) Peatfield, Lisa. ‘How the West Indies helped the war effort in the First World War’. iwm.org.uk 8/6/18 accessed 7/8/18

(5) Howe, Glenford D. ‘A White Man’s War? World War One and the West Indies’. Bbc.co.uk 10/3/11 accessed 7/8/18

(6) Rogers, Simon. ‘There were no parades for us’. The Guardian 6/11/02 accessed 8/8/18

(7) Cundall, Frank. Jamaica’s Part in the Great War 1914-1918. London: West India Committee, 1925. P.24.

(8) Howe, Glenford D. ‘A White Man’s War? World War One and the West Indies’. 10/3/11. Bbc.co.uk accessed 7/8/18

(9) Peatfield, Lisa.’The Story of the British West Indies Regiment in the First World War’. Iwm.org.uk 8/6/18 accessed 7/8/18

(10) Cundall, Frank. P.24.

(11) Ibid. P.28.

(12) Ibid. P.28.

(13) Ibid. P.28.

(14) Elkins, W. F. ‘A source of Black Nationalism in the Caribbean. The revolt of the British west Indies Regiment at Taranto, Italy.’ Science in Society 34:1 (1990): p.99-103. P.100.

(15) Lennon, Peter. ‘Dishonoured Legion’. The Guardian 7/10/99 accessed 8/8/18

(16) Peatfield, Lisa. ‘The Story of the British West Indies Regiment in the First World War’. Iwm.co.uk 8/6/18 accessed 7/8/18

(17) Johns, Steven. ‘The British West Indies Regiment Mutiny, 1918’. libcom.com 7/8/13 accessed on 7/8/18

(18) Elkins. Science in Society P. 99.

(19) Rogers, Simon. ‘There were no parades for us’. The Guardian 6/11/02 accessed 8/8/18

(20) Johns, Steven libcom.com

(21) ‘Caribbean participants in the First World War’. Memorial Gates Trust mgtrust.org accessed 7/8/18

(22) Ibid.

(23) Peatfield, Lisa. ‘The story of the BWIR in the First World War’. Iwm.org 8/6/18 accessed 7/8/18

(24) Elkins, W. F. ‘A source of Black Nationalism’ Science in Society P.102.

(25) Ibid, P.99.

(26) Johns, Steven. Libcom.com

(27) Ibid.

(28) Rogers, Simon. ‘There were no parades for us’. The Guardian 6/11/02 accessed 8/8/18